What Lies Ahead

Imagining the End of MTI Civilization and the Emergence of a New Equilibrium

Prologue: The Seeds of Crisis

“ . . . in the past lay darkness, confusion, waste, and all the cramped primitive minds, bewildered, torturing one another in their stupidity, yet one and all in some unique manner, beautiful.“ — Olaf Stapledon

Viewed in the gathering gloom of twilight the saga of technological humanity is not a triumph. It is a slow unravelling, a gradual, unrelenting, inevitable, decline.

Like a candle starved of air, the once-bright flame of the fossil fuel era flickered out, bringing to an end humankind’s mastery of the earth. The great cities of steel and glass, the great towers, crumbled; the machines fell silent. The song of civilization resounded once, twice, then faded away, a distant echo carried on the winds of forgotten ages.

This chronicle is not the story of the first women and men, nor even the last, but of those New People who came after — those who walked the ruins and ashes of a world remade not by human ambition and hubris, but by ancient, primal forces.

Seeking to understand and appease nature, in ages long passed humanity once revered old gods, symbols of the forces of nature. But over time these ancient powers eroded, forgotten, steadily replaced by a more and more unreasonable and unyielding faith in technology and progress.

What brought about modern humanity’s long, slow march downward? There was no singular, earth-stopping event; the end came in the form of a slow, grinding, centuries-long collapse. Like creatures drained of their lifeblood, earth’s great civilizations withered as the energy that powered modernity’s engines vanished from the planet’s veins. The downfall’s beginnings were uneven, with pockets of resilience and temporary hope remaining here and there. But as the centuries progressed, humanity’s fevered grasp on its fabled golden age loosened, slipped away. A world that once bent to the will of humans reclaimed itself. Oceans engulfed low-lying cities, swallowing them. Deserts replaced fertile plains. Life grew small, its rhythms once again quiet.

Here is the chronicle of those long, fading days — of the generations who witnessed the end of one world and the uncertain birth of another, of the emergence of a fragile New People who learned to once again walk lightly upon the earth, a future society, lucky enough to survive the trials to come, rooted not in a chimerical technological mastery of the earth, but in their adaptation to nature’s rhythms.

2040s-2060s — Tipping Points: Ecological and Social Collapse

By the early 2040s the economic strain brought on by the specter of oil depletion was too great to ignore. Oil production across the globe had peaked and was in steady decline. Easily extracted oil reserves were pumped dry, and costs of high-tech extraction of what remained had risen precipitously. Advanced countries who were absolutely dependent on oil for energetic and economic stability — mostly in the Global North — experienced severe economic disruptions and recession. What had been economic pillars of stability, the major oil companies, began to falter. Quite a few went bankrupt as the rest tried to pivot, recasting themselves as so-called “renewable energy companies.”

As the cost of mining and extracting oil and gas soared,and the energy return on energy invested fell, energy grids in almost all of the advanced economies struggled to maintain stable power delivery. A worried populace nervously watched the cascading failures of industries greatly reliant on oil, notably in the transportation, manufacturing and agribusiness sectors. The early-stage collapse of industrial agriculture and the massive disruptions to the food supply were particularly, ominously, unsettling. Consumers who had never experienced food insecurity faced huge increases in food prices.

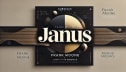

In addition to skyrocketing food prices, unemployment and social unrest increased. Panicked populations rioted. As political instability and civil unrest grew, governments struggled to manage their populations. Unable to meet the challenge, some governments collapsed or were overthrown. Across the globe autocrats and strongmen, promising relief to a desperate citizenry, replaced democratic governments.

Industrial civilization pressed on. Ecosystems, the natural world began to falter. Embodiments of earth, water, and sky, the old gods were forgotten.

The modern world had little use for myth.

The blooming global crisis did not affect everyone equally. Divergent paths began to appear. The rich, technologically-advanced regions initially fared better due to wealth and access to remaining energy reserves; consequently they were able to hold on to the remnants of modern civilization a little longer. Governments in North America, Europe, and China, Japan, South Korea, some parts of India, resorted to what amounted to short-term adaptations, prioritizing the transition to the “renewable” energies promised by wind, solar and hydroelectric. In the long run, however, the fossil fuel cost of this strategy became brutally apparent. The switchover was flawed from its inception, and, in any case, insufficient to offset the overall loss of energy-dense fossil fuels.

While all this was going on, many rural areas faced almost immediate collapse, even in the richer nations: their dependence on long-distance supply chains and industrial agriculture proved too great an obstacle to overcome.

The developing nations and vulnerable regions — mostly in the Global South — also faced rapid decline and collapse. Sub-Saharan Africa and parts of South Asia and Central and South America were especially hard hit, since they were heavily dependent on imported energy and food. Governments in these regions simply didn’t have the resources to transition their economies, or pivot toward renewables. Mass famine and drastic energy shortages resulted in almost complete breakdown of some state structures.

Paradoxically, a handful of rural and remote areas demonstrated some surprising resilience, mostly due to their long-standing practices of subsistence farming and low reliance on external inputs. Nonetheless, pressure from high populations coupled with frequently violent resource competition threatened to overwhelm even these traditional systems.

The climate crisis, brought on by humanity’s profligate fossil fuel use and resultant burgeoning population, became a catalyst for collapse.

The frequency of extreme weather events significantly increased in the mid-twenty-first century, with hurricanes, floods, droughts and wildfires exacerbated by accelerating global warming. Again, the Global South was hit especially hard, as coastal cities and low-lying regions faced repeated devastation. Battered infrastructures crumbled, and powerless governments were unable to cope with unprecedented mass displacements.

Severe floods and droughts in key agricultural regions — especially in the American midwest, India, Ukraine, and China — led to repeated crop failures. With the collapse of industrial agriculture on the near horizon, the threat of starvation became real, and competition for fertile lands increased sharply, leading to more political unrest.

Almost unnoticed in the chaos, as traditional infrastructures began to falter and fail, small isolated communities appeared, rejecting modern conveniences, choosing instead to live close to the land. For decades these New People had been on the margins of society, alarmed at the path civilization was taking. Modeling a future that most were not yet ready to embrace, they were ignored by almost everyone.

2070s-2100s — The Spiral of Descent: Famine, Migration, Conflict

Late in the twenty-first century, in the midst of severe energy shortages and ever-more-violent weather events, global trade collapsed and trade networks disintegrated. Essential goods — food and medicine — were increasingly scarce. Governments stood by helplessly as shortages caused humanitarian crises. Following the sharp contraction of the international economy, many nations retreated into isolationism.

Having failed due to energy constraints, industrial agriculture’s food production was by now essentially nonexistent, forcing regions to rely on imports or unsustainable farming methods which quickly collapsed under environmental pressures. Traditional farming techniques fell far short of meeting the food demands of a still-huge population. And the loss of arable land only added to agriculture’s woes. Perennially fertile areas, like the Mekong Delta, the Nile Delta and other coastal farmlands and river deltas, were lost to rising seas and saltwater intrusion, further reducing global food production capacity. By 2100 the world was witnessing increasingly widespread famine and mass casualties.

Large-scale migrations were by now underway, as millions sought resources and stability. Disoriented and terrified populaces fled heavily affected areas, seeking regions with more resources. Conflicts over the remaining resources exacerbated the crisis and caused further suffering.

And adding to the migrations underway, millions more migrated inland, escaping the coastal areas’ rising sea levels and further straining overburdened governments. Large areas of major coastal cities such as Miami, New York, Tokyo, and Shanghai, feeling the effects of rising waters, were partially submerged or uninhabitable due to flooding and storm surges. Municipal and federal governments were unable to bear the costs of constant reconstruction, which hastened the decline of both local and global economies.

During this period, some regions simply became too hot for humans, creating uninhabitable zones. Parts of the Middle East, North Africa, South Asia and Central and South America were especially affected. Facing extreme heat stress and water and food shortages, megacities like Karachi, Delhi, Riyadh, and Mexico City experienced mass exoduses and migrations.

At the same time, vector-borne diseases increased dramatically as warmer temperatures allowed disease-carrying insects and bacteria to thrive. Malaria, dengue fever, and cholera spread into regions where they had rarely been seen before. To add to the misery, by this time most of the globe’s already-fragile health systems had collapsed, increasing mortality rates and further destabilizing regions.

While humans were struggling with their own existential crises, the planet’s ecosystem was reconstructing itself. Brought on by the climate crisis, the world that had nurtured humanity for millenia was experiencing an ecological breakdown, fragmentation and reformation.

Large areas of the Amazon rainforest, Southeast Asia, and the African Congo faced rapid deforestation and dieback, becoming vast savannah-like plains. Once crucial carbon sinks, these areas became sources of carbon emission, worsening the global climate emergency.

The Sahara, Gobi, and other deserts expanded, and in doing so consumed arable land, forcing even more communities to migrate. More desertification in areas like the Sahel accelerated conflicts over dwindling resources, causing yet more political instability, ethnic strife, and mass casualties. Croplands in southern Europe and parts of the US and Australia dried out, becoming infertile.

In some regions most hard-hit by drought and famine, whispers of the old gods began to surface. As the promise of a technological paradise crumbled, some sought solace in near-forgotten rituals, looking to reconnect with the ancient forces their ancestors once knew.

In what was to become the most significant migratory shift in a hundred thousand years, as temperate and tropical regions became less habitable, human migration patterns shifted northward and southward. Reacting to the shift in habitable zones, humans migrated toward the poles. While Northern Canada, Scandinavia, Russia, and parts of the southern Andes became more temperate, their ability to sustain humans was limited, as the new arrivals soon learned. The influx of human populations into previously colder, sparsely populated regions created ecological chaos. People arriving in these areas tried to introduce new agricultural systems; but they soon learned that the Arctic and sub-Arctic regions’ fragile ecosystems were poorly suited to large-scale human settlement. Crop yields were unreliable; nor was there the biodiversity needed to support sustainable ecosystems. And the wholly foreseeable thawing of the globe’s permafrost regions released an enormous quantity of carbon dioxide, adding to the climate disaster.

Water became an especially fought-over resource, with water wars becoming commonplace.

Glacial melt in the Himalayas and Andes had greatly disrupted nutritive sediments and reduced water flow to major rivers like the Ganges, Brahmaputra, Yangtze and the Amazon. Billions in South and East Asia and South America were impacted. Conflicts, then wars broke out over dwindling freshwater sources, and tensions between India and China, both still possessing ageing nuclear weapons, were at a flashpoint. Nations in the Middle East, still sitting on vast oil wealth, invested in desalination technologies, hoping to create yet another monopoly on a fluid indespensible to humanity. But, as before, the long-term energy costs of this technology were too high, and the industrial infrastructure necessary to keep these desalination plants going was non-existent. The effort was abandoned.

As the twenty-first century drew to a close, the New People were no longer a fringe movement. Accepting that scarcity was the new norm, and adapting to the hardship that was all around, a growing faction of humanity turned to almost-forgotten agricultural techniques. These early- adapters fared better than others, and, though they were too busy surviving to notice, they were laying the groundwork for a new social order.

2100s-2200s — Fragments of Survival: Adaptation and Divergence

The twenty-second century saw the re-emergence of a millennia-old political form: the city-state. A few fortuitous, well-placed areas for a time held on to a small semblance of advanced civilization. These remaining technological islands, mostly coastal cities or resource-rich areas, retained vestiges of technological civilization and persisted through careful management of resources and knowledge preservation.

One such outpost remained in Iceland, supported by its geothermal potential. Several other, very sunny, solar-friendly regions were also able to maintain partially functioning power grids, some manufacturing, and a limited form of industrial agriculture, though on a much reduced scale than before.

Life in these regions, for a while, at least, resembled a form of neo-feudalism — a small elite jealously controlled the remaining technology and energy production, while the majority of the population lived in a more primitive condition. The leadership class in these regions made intentional efforts to preserve knowledge, either through oral traditions or small groups of scholars, who kept archives of science, medicine, and technology. For a time these communities functioned as knowledge banks.

Like dukes and princes of more than a millennia past, in these city-states elites retreated into fortified, self-sustaining strongholds with some access to advanced technologies like vertical farming, water desalination, and even in a few instances, AI-based management systems. These holdouts persisted for several decades, one or two for almost a century. But their existence was fragile, and the resources needed to keep them going grew ever more scarce, finally disappearing altogether. Like societies everywhere else, they were energy reliant and eventually fell into decline as resources ran out.

Regions diverged in their response to the ongoing crisis. The New People stood out, thriving where others faltered. For them the collapse had accelerated a transformation, a definitive break from the fossil-fueled past.

Settling in parts of the world where agriculture was still possible, their resilient rural communities resembled those once common in the pre-industrial era. Focusing on crop rotation, seed-saving, and permaculture principles, and making do with limited trade and relying on human and animal-powered labor, these partially regressed societies reverted to subsistence farming, producing just enough food to sustain their populations.

Stressing community collaboration, resource-sharing, and sustainable practices, these settlements ordered their affairs through community-based governance systems with a focus on the traditions and cultural practices that surrounded agriculture, farming, food storage, water management and the natural world. Eschewing centralized state power, elder Councils of men and women presided over a communal decision-making process. Localized economies developed, and small-scale trade networks were established between communities, which formed regional alliances to share resources and knowledge.

As long as these rural hamlets were left alone, they lived in relative peace and stability; but they were threatened by contact with the frequently violent roving bands of displaced refugees.

During this time, some societies in world regions with failed governments and limited resources disintegrated entirely. Lacking a functional state, these locales descended into violent anarchy, marked by tribal warfare over the few resources that remained. Warlords and gang chiefs led bands of marauders who preyed on anyone who had more than they did. That these areas where chaos ruled experienced large-scale migration is no surprise.

Some very remote and depopulated regions saw a hunter/gatherer revival, with small bands of post-collapse humans relying on foraging, fishing, hunting, and basic toolmaking. Settling in rich ecological areas where agriculture was unsustainable (or unnecessary due to population collapse) and protected from marauders by deep rivers or high mountains, these bands thrived in forests and river valleys, places with fertile ecosystems, where they developed new cultural norms and survival practices that emerged from their nomadic lifestyle. These groups began the process of relearning and transmitting to their offspring sophisticated knowledge of local ecosystems, returning to a deep connection with the land similar to Paleolithic or Neolithic societies.

Ceremonial practices, storytelling, and shamanistic traditions became central to these societies. Oral traditions preserved knowledge across generations, and these communities adopted spiritual or ecological philosophies that emphasized harmony with nature, survival skills, and reverence for the earth. The shaman, as a mediator between the community and the natural world, played a vital role.

2200s-2300s — The Age of Reinvention: New Modes of Existence

By the end of the twenty-third century global population stabilized at a drastically reduced level, perhaps two-to-three percent of pre-collapse numbers.

The few remaining technological city-states had failed as access to remaining resources dwindled to nothing. Some fragmented knowledge was preserved, but much of the scientific understanding of the pre-collapse world was lost. These areas, where the faint glimmer of modernity once remained, slowly merged with the more primitive societies that surrounded them.

Most of the planet’s remaining human occupants — a mix of subsistence farmers and hunter/gatherers — inhabited rural areas. As the remnants of modernity faded away, new forms of human expression and culture emerged. Some groups maintained the traditions of modernity; their music, dance and oral storytelling echoed the distant past. Others, notably the hunter/gatherer societies, created new identities, dominated by ecological, animistic and spiritual worldviews.

The hallmarks of the post-fossil fuel age were regional variation, cultural resilience and ecological knowledge. Societies adapted to resource availability, environmental conditions, and the social structures that appeared as a response to the crises they faced.

By the twenty-third century the walk-lightly-on-the-earth lifestyle of the New People was the dominant mode of existence. No longer a subculture, they had fully embraced low-energy, no-tech, sustainable practices, living in balance with nature and developing their own rituals, philosophies and governance structures. For the New People, the reversion to a simpler, more sustainable way of life was not a tragedy, but a long-awaited transformation toward a more harmonious existence.

But even for them, though much of the chaos of the collapse period was by now passed, the survivors faced a diminished world.

Biodiversity loss was extreme. Ecosystem collapse due to warming, pollution and habitat destruction had wreaked havoc on the planet’s biosphere. The loss of key species, such as pollinators and apex predators, had destabilized ecosystems, making even subsistence agriculture and hunting and foraging problematic. Humans struggled to adapt.

Many species had gone extinct; but some resilient species of plants, insects, animals, reptiles and fish survived. Humans slowly learned to adapt to the reality of new ecosystems.

Ecological collapse had fragmented human populations. Communities were cut off from one another, separated by deserts, wastelands and flooded coastlines. As in ancient times, long-distance travel became dangerous, even impossible, due to extreme weather and other environmental risks. Small, scattered populations became more-or-less permanently isolated.

A New Equilibrium: Rebirth Amid Ruin

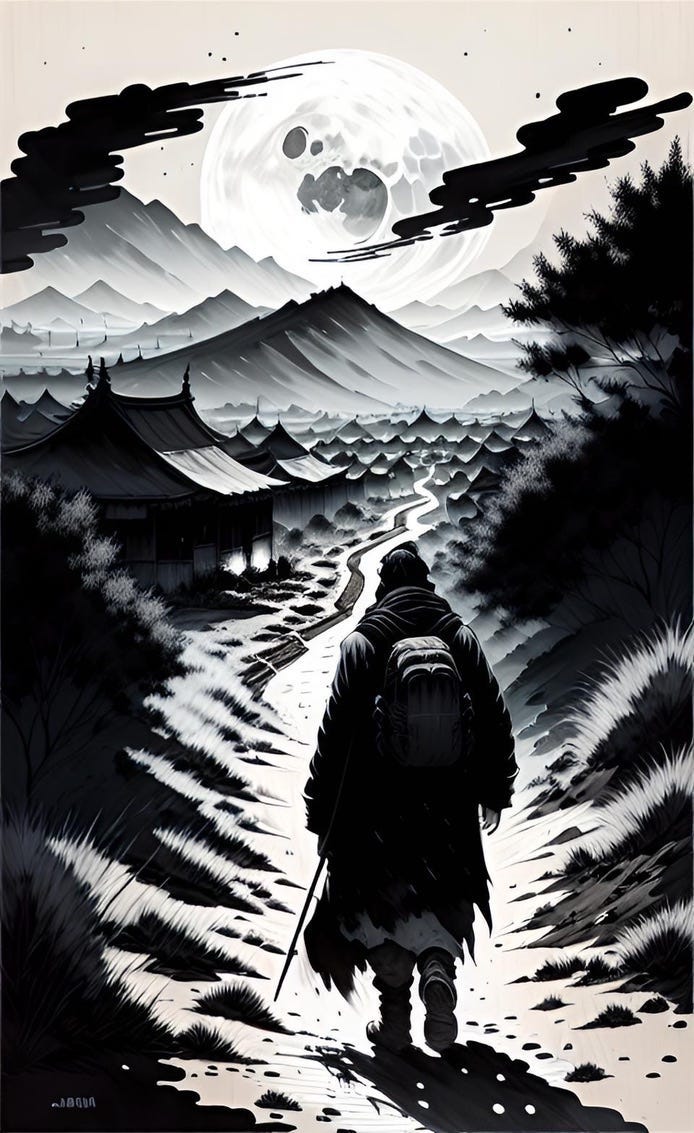

Was humankind’s elegiac song a requiem? Or was it a prelude to a great new symphony, an adagio introducing a new glorious movement? On its face, the scattering of humanity and the reemergence of ancient survival practices might seem to be a regression. Seen from the perspective of modernity, it seemed a devolution. But was it? Though the practices were superficially similar, humanity’s New Barbarism differed in important ways from that of its distant ancestors. The first practitioners of ecosensible living did so almost unconsciously, seamlessly, almost effortlessly living in response to the demands of the environment, within the limits nature set for them. On the other hand, the New People who roamed the planet fifty millennia later had in their past the experience of the rise and fall. To be sure, conscious memory of the towering accomplishments of modernity were mostly gone. Only crumbling ruins remained to hint of the great ambitions that brought about their creation.

But stories, tales, new myths told around new fires recalled the greatness — and huge folly — of which humans are capable. New traditions and myths carried forward lessons learned, hopefully not to be again forgotten. Humankind’s twenty-fourth century return to the ways of the misty past was not a mere slip into senescence and decline, but a rebirth, a renewal.

In the aftermath of population collapse, human society began to reach a new equilibrium. Humanity began to learn, once again, to live in balance with what was a changed natural environment, forever altered by climate. Like the plants and creatures around them, humans learned to adapt, learned to live in harmony with new systems. The small scattered bands were acutely, viscerally aware of the implications of exceeding the biosphere’s carrying capacity. They began to adjust to a new reality.

Living by sustainable hunting, gathering, and low-tech agriculture, these New People superficially resembled early human civilizations, with their emphasis on communal living, deep ecological knowledge, and a symbiotic relationship with the land. But they were different. Their situation was the product of human blunder, and they knew it. Their ancestors were guilty of a near fatal miscalculation: ignoring the extistential importance of living within the limits of the environment from which they came. A self-inflicted wound, their overshoot had brought about the climate disaster which had accelerated the collapse of their civilization; but it also made possible the reshaping of humanity.

Though forced to adapt to an increasingly hostile environment, humanity was, nonetheless, offered a second chance. A brief window of opportunity flashed open. If only they were able to take advantage, to rapidly shift their lifestyles and social structures in response to the new climate realities!

Literally walking in the ashes of the old world, the New People emerged as a living testament to humanity’s resilience. Their way of life exemplified how human societies might yet endure, even thrive, in equilibrium with the natural world.

But balanced on a razor’s edge, the New People walked a perilous path. Would the necessities of human survival stand in the way of the planet’s ecological rebirth? Could humanity learn to live simply, to find meaning in the mere enactment of the processes of everyday life? Or would the species once again revert to hubristic grandiosity, forgetting that humans are, at their core, animals, who, like all animals, must live within the limits of nature?

Though the laws of nature may be inviolate, there is still some leeway along the way. The earth will no doubt continue to exist until the sun expands and engulfs it a few billion years hence. The planet and, most likely, a wide array of creatures and plants along with it, will persist for a time. Whether or not Homo sapiens is a part of this future history, however, is not a determined fact.

What this future looks like depends to a large extent on the choices that humans make. There is no telling what will happen. Will the old earth gods be recalled? Was the end not the end? Was it a new beginning?

The powerful sense of hesitancy, of uncertainty that characterized the plight and reemergence of twenty-fourth century humankind was captured by a brilliant pre-collapse poet who wrote about the return of the old gods, the old ways.

See, they return; ah, see the tentative

Movements, and the slow feet,

The trouble in the pace and the uncertain

Wavering!

See, they return, one, and by one,

With fear, as half-awakened;

As if the snow should hesitate

And murmur in the wind,

and half turn back;

These were the “Wing’d-with-Awe,”

inviolable.

Gods of the wingèd shoe!

With them the silver hounds,

sniffing the trace of air!

Haie! Haie!

These were the swift to harry;

These the keen-scented;

These were the souls of blood.

Slow on the leash,

pallid the leash-men!

Ultimately, the end was not the end. It was a new beginning. In the twenty-fourth century humankind stood at the precipice of a new era. The echoes of modernity ringing ever more faintly, faded away. The old order was ruined, dead; but from it rose the promise of a new beginning. Like the poet’s “Wing’d-with-Awe” gods returning with uncertain steps, humanity tentatively trod ahead. The most difficult of challenges lay before them. Mistakes would be made. The consequences of every misstep would be far-reaching.

The task of rebuilding a world that had been shattered by hubris would be humankind’s defining moment.

This speculative arc from energy depletion to neo-feudalism captures something most policy discussions miss entirely. The faded transition you lay out between collapse stages feels more realistic than the usual binary apocalypse/utopia framings. I've spent time in ag communities experimenting with permaculture, and the tension between maintaining complexity vs accepting simplification is already palpable in conversations about food security. The detail about Arctic ecosystems being unsuitable for refugges despite warmer climates is the kind of second-order consequence that gets overlooked when people assume technology will route around biophysical limits.